By: Babson Ajibade*

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt in various ways around the world. As governments instituted lockdowns, individuals and communities took own steps to mitigate the impact of not just the virus itself, but also of the shortage in supply chains for the needy. While the impacts of the virus itself are devastating for many developed nations, in developing countries like Nigeria, it has been more in the socioeconomic sense.

The reason for this is simple. In most of Africa, social, health and sanitation services are largely undeveloped, just as supply chains are very informal. Furthermore, most of the working population are self-employed in informal sectors, where wages are earned daily, and savings are impossible, since individuals live subsistent lives.

The Pandemic Situation in Nigeria

As at Sunday 24 May 2020, Nigeria has only 7,526 cases and 221 deaths, which is not yet a “tragic dimension” in a population of 200 million. Still, there are lockdowns, closures of state boundaries, closures of markets, curfews, and the shuttering of businesses across Nigeria.

In the period of lockdowns, those in the informal sectors earning daily wages – like in the arts and cultural sector - have no salaries coming. They have no possibility to earn anything without going out to trade, hawk petty goods or solicit work at construction or other sites. For this category of persons (and they are in the several millions) when they don’t earn money in any one day, they have nothing to feed their families the next. It is that bad, and there is no government office or agency mandated to help.

Some Nigerian state governments made attempts at distributing palliatives of food, meant to help the most vulnerable. But these palliatives were so meagre that some neighbourhoods in Lagos claimed they received the equivalent of a loaf of bread for a few dozen people. To spite the officials that distributed the bread, young men kicked the loafs as soccer balls in the streets, and poured the distributed grains of rice away. They were angry at the small portions of food supplied to whole neighbourhoods of needy people.

Then, of course, the regulations from the government were that people needed to wash hands regularly and stay indoors, in addition to social distancing. But there is no portable water to wash hands, and national electricity is too often absent, to enable people entertain themselves by television or even cool off with an electric fan or air conditioner in the tropical heat.

For the most vulnerable and needy around Nigeria, salvation has been coming from spirited individuals and organisations that provide free food and other supplies. In cities like Abuja and Lagos, dozens of individuals and groups have hotlines that very needy people could call to get free supplies. It has been so amazing to see help coming from previously unknown quarters for millions of vulnerable people. When I shared this situation with a friend who lives in the UK, he wondered why people in Nigeria did not plan for the pandemic. But I told him that most Nigerians cannot afford to plan because they have no saved-up finances, in the first place, because they earn only enough to live one day at a time. Since February 2020, I, like many others, will package some supplies and give to a few needy persons. Now, those that give to others are not necessarily wealthy or that they can really afford to. It’s more because they cannot afford to not give to the needy. To drive this point home, I shall narrate the recent experience of a friend, Renee. She was home, one afternoon, when a neighbour’s son walked in to see her. As they got talking, the boy said to her: “My mum will be too ashamed to tell you this, but I will tell you. We have not eaten for two days”. The import of these heart rendering words will surely compel anyone to give. She promptly gave the boy part of her own little supplies. This is the amazing giving spirit that has sustained millions of Nigerians through these pandemic times.

The Response by Arts Schools

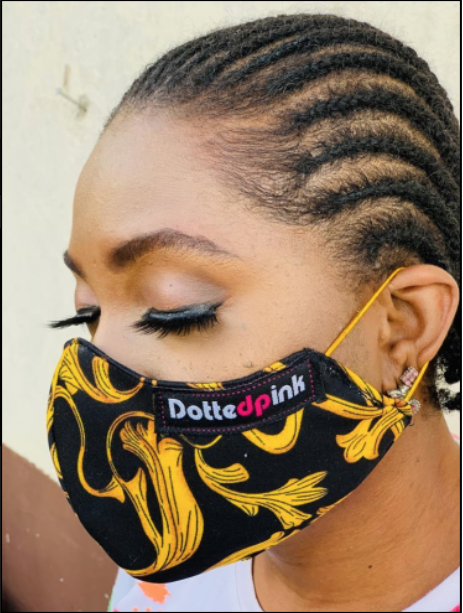

Renee, wearing one of her masks.

In the city of Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria, there are two art schools run by the Cross River University of Technology and the University of Calabar. Most of the visual artists practicing and teaching within the city were trained in these art schools. The city also hosts the yearly Carnival Calabar, which takes place in December, bringing tourists and culture lovers from around the world. So, in a certain sense, Calabar is a culturally vibrant city where art education thrives and various creatives operate and earn their living.

Umana in one of her colorful masks.

The pandemic has relegated the art economy of Calabar, where the impacts have been somewhat different from most of Nigeria. First, of the country’s 36 states, Cross River is one of two yet to record a COVID-19 case. For this reason, there has not been an actual lockdown, though offices, schools and religious centres were shut. The shutting of offices and businesses meant the dwindling of money in circulation. While traders continue to record low sales, artisans and people in the creative industry generally have been the most affected, because their artistic services and goods are not considered essential as food. Thus, visual artists, artisans, tailors and those in the fashion industry suffer severe losses of livelihood within this pandemic period. Second, the dynamic Governor of Cross River, Ben Ayade, was the first to enforce the use of the nose masks in Nigeria. With the scarcity of N95 masks earlier in 2020, couples with the cost of importing them, the Governor not only enforced the use of masks, but also spearheaded the production of homemade masks with locally available fabrics. He engaged hundreds of tailors to produce millions of masks that were shipped to other Nigerian states.

Now, this last point, of producing and enforcing the use of nose masks has had a most unintended consequence in the city of Calabar. Dozens of young creative people, whose livelihoods were “taken away” by the pandemic, are now making income from the same masks instituted to keep the virus out.

A New Creative Industry For Artists

Cilliashinda, wearing one of her mask designs at her recent wedding.

Many, like Umana Nnochiri, Joy Eroma, Dorcas Bassey and Renee Iso (mentioned earlier), are textile and fashion designers, sewing and producing for a variety of clientele before the pandemic. Having been significantly robbed of their livelihoods by the pandemic, now, they are all taking and supplying small, medium and large orders for homemade nose masks to fight the virus. Some of the masks they make are adapted to specific contexts. For instance, COVID-19 regulations limit gatherings such as burials and weddings to just a few persons who must wear nose masks. Since nose masks make wedding vows clumsy to say, Cilliashinda and Ene, who got married on 9 May 2020, imprinted “I Do” on their masks for the short ceremony. Other masks are designed with concealed slots for the mouth, and can be used in situations of consumption.

The young creatives in Calabar are using cotton and other African fabrics to produce stylish, colourful and functional nose mask designs that are helping several communities. The N95 mask sells for up to N3800 (about $9.5), which is very unaffordable by most Nigerians. In contrast, the homemade nose masks, depending on materials, sell for between N100 and N1000 (about $0.25 -$2.5), which is comfortable enough for all pocket sizes. In these most challenging times what one can observe is that the people leading this new nose mask entrepreneurship in Calabar are young, and they are women – which is, in itself, a positive development, considering they live in a male-dominated society. In that context, the pandemic has definitely reconfigured a new “normal” in society, requiring adherence to distancing, isolation, hygiene and masking regulations. However, from behind the back of male-domination, this “new normal” has opened up socioeconomic spaces for young Nigerian women to take charge and lead efforts that positively impact their communities.

Some of the masks like this one are designed with concealed slots for consumption.

Unlike previous times where they needed to walk around to solicit mostly male patronage, now, seated in their own socially distanced spaces, these same women creatives are taking and supplying orders to people they never even met. While the nose mask entrepreneurship of women creatives in Calabar will not be a permanent feature, it at least provides us a window into how society is shaping in these times. At the same time, it evidences the lead efforts through which women are impacting their communities in a Nigerian city, during these most challenging times.

Dorcas, wearing a nose masks design that allows the wearer to eat.

Joy, wearing a plain-colour mask design she made.

*Babson Ajibade

Babson Ajibade is Professor of African Visual Culture and Visual Anthropology in the Department of Visual Arts and Technology, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Cross River University of Technology, Calabar. He holds a PhD (Scene Design) from the University of Calabar and a PhD (Social Anthropology) from the University of Basel, Switzerland. Funded with a grant from the Swiss Government (2004), his Doctoral work at the University of Basel was the first PhD on the popular video films. A national Consultant to organisations such as Family Health International (FHI), the National Agency for the Control of Aids (NACA) and the Malaria Action Plan for States (MAPS) on Social and Behaviour Change Communication (SBCC), Review of Strategy Documents and media materials development and production. He is a Member, Technical Work Group (TWG) for the National HIV/AIDS Strategic Framework (NSF). He was Consultant (Visualisation) to the online Project, Trading Faces: Recollecting Slavery Project, a consortium project developed by Future Histories, Talawa Theatre Company and the V & A Theatre Collections – supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund and Access to Archives, London. His research interest is visual culture, popular culture, popular arts, media and youth studies. A painter, he has held exhibitions in Lagos, Benin, Calabar, Basel, and Belgium. He is the author of several scholarly articles in textbooks and academic journals. His textbooks include Promotion, Arts and Design: an Integrated Approach to the Basics (1999)and Audio-Visual Media and Techniques in Public Relations (2002) and Creative and Media Arts: A Practical Source Book (2014). His latest book is Video Films in Nigeria: Citizenship and Contested Identities (Forthcoming). He is Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Science, Engineering and Technology.

-

Ajibade, B. (2020, May 25). The Nose Mask Entrepreneurship of Women Creatives in Calabar. Creative Generation Blog. Creative Generation. Retrieved from https://www.creative-generation.org/blogs/the-nose-mask-entrepreneurship-of-women-creatives-in-calabar